The “EV slowdown” is overblown. It’s internal-combustion cars that are on their way out.

[Published June 2024 on InsideEVs. For a more interactive data experience, check this story out there.]

The last several months have been messy for the electric vehicle industry, to put it mildly.

Major players like General Motors, Ford and Mercedes-Benz are pumping the brakes on their electrification efforts, citing uneven and unpredictable consumer demand. Many drivers remain hesitant to go electric because they’re worried about a lack of charging stations and insufficient range.

Tesla, the longtime leader in the space, could’ve led the charge this year with new and updated models but is focusing on AI and robotics instead. After years of meteoric growth, the EV powerhouse reported an 8.5% slump in vehicle deliveries in the first quarter of this year. Lately, the conversation around the electric car market has been defined by bad vibes and a murky outlook.

However, when you look past the gloomy headlines and take a broader view, a clear trend emerges: The internal combustion engine is dying out.

Electric and hybrid vehicles are gradually—and in some parts of the world, rapidly—edging out sales of conventional, non-electrified gas-guzzlers. Experts say that’s a big win for the planet. And even if some automakers are now announcing new and updated engines to stay competitive if full EV adoption takes longer than expected, it’s hard to dispute the trends that point to the end of the gas-burning era.

“The market is just looking way too short-term at all of this,” said Daan Walter, principal at RMI, a nonprofit research organization focused on clean energy. “It’s really over for the combustion engine.”

Charting The Decline Of Internal Combustion

Sales of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles peaked globally in 2017 and have been in decline ever since, according to the research firm BloombergNEF’s (BNEF) latest Electric Vehicle Outlook report. The total fleet of ICE vehicles, including hybrids, on the world’s roads will peak in 2025. By 2027, oil demand for road transportation will also peak, BNEF projects.

By that year, plug-in (and even hydrogen-fueled) vehicles across segments will help displace 4 million barrels of oil each day, according to the report. That’s roughly the annual oil consumption of Japan.

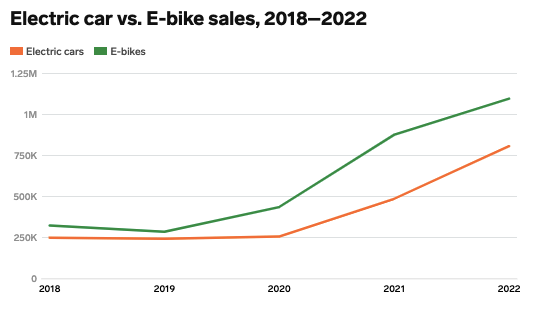

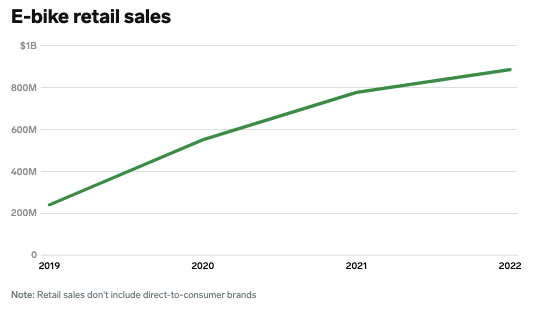

As sales of old-school cars and trucks have fallen, EV sales have skyrocketed. In 2023, some 14 million electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles were sold globally, amounting to 18% of total passenger vehicle sales, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). That’s a gain of 3.5 million, or 35%, over 2022. Take a longer view and the numbers get even more eye-popping. As recently as 2016, roughly 700,000 plug-in cars were sold worldwide, according to the IEA. Put simply, annual electrified vehicle sales have exploded by 2,000% in well under a decade.

The EV transition is here, but it’s far from evenly distributed. China and some Nordic countries are eating much of the world’s lunch when it comes to the uptake of EVs. Still, U.S. sales of ICE vehicles have trended downward as well.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the market share of conventional gas-powered cars sank to its lowest point ever in 2023: 84%. Meanwhile, hybrid, plug-in hybrid and fully electric vehicle sales grew to an all-time high of 16% of the U.S. market. Pure EVs, or battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), accounted for a record 7.6% of new vehicle sales last year.

The U.S. lags far behind China, where aggressive industrial policies and intense competition have catapulted EVs to 50% market share in relatively short order. Regardless, things are moving in the direction of more electrification here too.

The EV Market Will Keep Growing, Despite Hiccups

Despite what you may have heard, EV momentum did not fall off a cliff in 2023; it merely slowed to a pace below previous levels of spectacular growth. Yearly sales of plug-in cars are projected to more than double over the next four years, reaching 30.2 million in 2027, according to BNEF. Sure, the 21% average annual rate of growth worldwide over that period won’t be quite as fierce as the 61% witnessed over the last four years. But is this doomsday for electric cars? It sure doesn’t look like it.

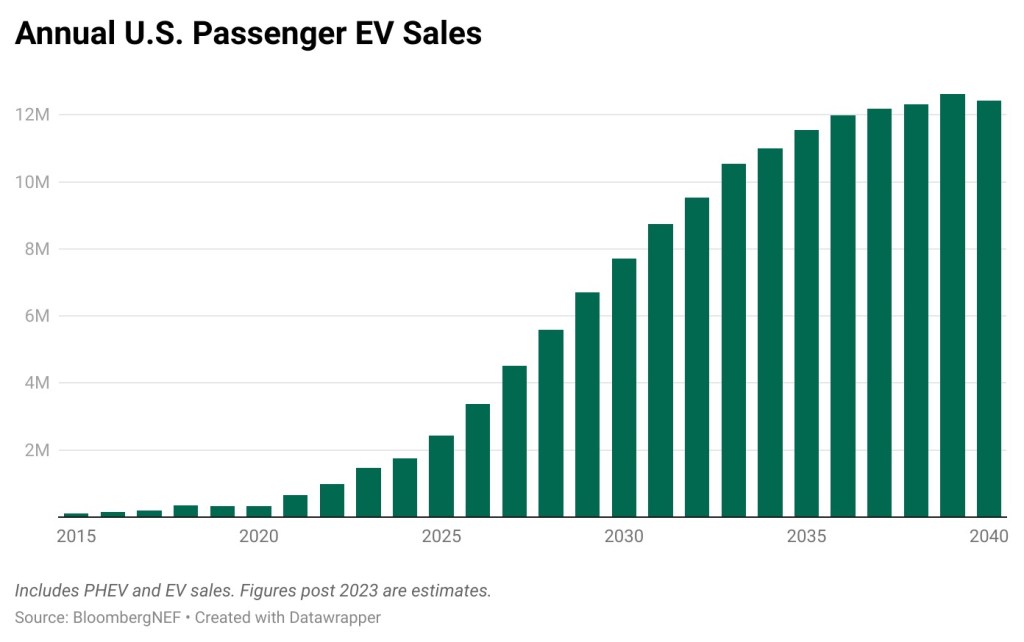

EV sales will keep climbing over the long term, giving ICE vehicles no viable path back to 2017 levels. According to BNEF, sales of plug-in cars will hit 42 million in 2030 (45% of sales) and 73 million in 2040 (73% of sales). And that’s assuming no new policy interventions.

Government policy—in the form of both carrots and sticks—has been crucial for driving the EV transition thus far and will continue to play a large role in some parts of the world, experts say. But other key tailwinds are coming into play besides generous subsidies or looming ICE vehicle bans.

One big one: The economics of both making and buying EVs have gotten better and better as the industry has scaled up. Case in point: The new BYD Seagull hatchback, from China’s biggest EV maker, sells for as little as $10,000 in its home country. As EVs fueled unprecedented demand growth, lithium-ion battery pack costs have plummeted from some $1,400 per kilowatt-hour in 2010 to $139 in 2023, according to BNEF, which says costs should fall further.

Continued gains in EV affordability will be key for getting more buyers on board worldwide. EVs have historically skewed toward the luxury end of the spectrum in the U.S., though prices have trended downward. And some models already cost less than gas-fueled counterparts when you factor in the total cost of ownership. That’s because electric cars require less maintenance and electricity generally costs less than gas.

The next “inflection point” will be widespread price parity in upfront cost, Walter said. That milestone, when a buyer can understand that an EV will save them money without thinking too hard, has been achieved in some leading markets but not yet in the U.S. “That is really when you see the market go into overdrive,” Walter said.

What’s more, studies show that once someone buys an electric car they rarely switch back to gas. EV drivers love the savings; the ease of charging at home; and the quietness and smoothness of the ride.

Another emerging driver of change: competition and the fear of falling behind. Unlike the early, policy-driven days of the EV transition, automakers themselves are aggressively moving the ball forward to stay competitive, said Corey Cantor, a senior EV analyst at BNEF. For car companies, the cost of inaction is higher than ever.

“The further we get into this decade, the more the winners and losers will probably differentiate themselves,” Cantor said. “So if you’re an automaker, you can’t afford to not have a BEV strategy from this point.”

So What About That EV Slowdown?

To be sure, it isn’t all sunshine and rainbows in EV land. The long-term global picture looks rosy, largely because of China’s ferocious pace of growth. But individual markets, including the U.S., are hitting near-term speedbumps.

In the first quarter of this year, U.S. plug-in car sales grew only 4% year-on-year, according to BNEF. That’s mostly a Tesla problem that could stem from its aging vehicle lineup, caustic chief executive, or both. Companies like Ford and GM have actually seen tremendous year-over-year gains on the EV front, despite their bellyaching.

The Hyundai Motor Group umbrella, which encompasses the Kia and Genesis brands, is also seeing immense success. Any of those three automakers could see 100,000 U.S. EV sales in a year, a milestone only Tesla has achieved here so far.

Plug-in car sales in the U.S. will end the year up 20% over 2023, BNEF says, less than the 32% it had previously projected. Still, it expects plug-in cars to make up 29% of the U.S. vehicle market by 2027. Looking out a few years, the health of America’s EV transition hinges on whether cheaper models materialize in a meaningful way, said Cantor. Think a range of different models in the $25,000-$32,000 range, after incentives. Those kinds of vehicles are in the works from Ford, GM, Jeep, Kia and others.

It’s normal for a new technology to see explosive adoption at first, followed by a slower rate of growth. It’s easier to increase sales by 60% or 70% when last year’s sales were relatively small. And it’s harder to sell mainstream buyers on novel tech once the early adopters have run out.

Still, climate experts are urging policymakers to do more on EVs. As the effects of climate change become more palpable than ever, the world is still spewing record levels of carbon emissions. And in the U.S., the transportation sector’s CO2 emissions are rapidly bouncing back from their pandemic-induced lows. Most climate scientists believe humanity is headed for disaster if these trends aren’t reversed soon.

“EV’s are yet another classic technology revolution,” said RMI’s Walter. “The difference now with climate tech is that it’s a technology revolution—but with a deadline.”